By Dr. Salika Lawrence

What do we mean by “inquiry-based teaching”?

Inquiry-based teaching is a student-driven approach where learning starts with questions, curiosities, and real problems. This approach is not guided by a pre-taught answer. Students gather and analyze evidence, test ideas, and communicate what they discover. The teacher is a co-creator of knowledge working alongside students in the classroom as a community of learners. One widely used framework is Barbara Stripling’s Inquiry Model, which organizes learning into recursive phases: Connect, Wonder, Investigate, Construct, Express, Reflect. It’s been popularized in K-12 through the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources (TPS) program.

Inquiry-based teaching connects naturally to other approaches you may already use:

Project-Based Learning (PBL): Students learn by engaging in meaningful projects designed around a driving question and a public product; PBLWorks lays out the core design elements and teaching practices as well as examples from real classrooms.

21st-Century Skills: Students draw upon their content knowledge to integrate ideas through collaboration, communication, creativity, and critical thinking, as outlined in the P21 Framework (now hosted by Battelle for Kids).

Mixing student inquiry with clear, teacher-directed guidance leads to strong student outcomes. This means that teachers benefit when inquiry is centered in the curriculum, and they receive support through teacher modeling, mini-lessons, scaffolds and routines.

Two key components of inquiry-based teaching

While “student-driven” is the goal, inquiry doesn’t happen by accident. Teachers make it successful by intentionally designing learning in two ways:

- Problematizing the topic

At its core, inquiry asks students to view a subject as a real problem or challenge to explore and communicate with others through use of disciplinary practices, not just a set of facts to memorize. For example:

- In history, instead of telling students what happened during the Boston Tea Party, frame the lesson around: “Why might colonists risk breaking the law and angering the most powerful empire in the world?”

- In science, instead of simply teaching photosynthesis, ask: “Why do plants matter to life on Earth, and what would happen if they disappeared?”

When teachers frame content this way, students have a reason to investigate, compare sources, and generate their own explanations. Even small shifts such as turning a reading passage into a “What happened before/after?” puzzle can spark curiosity and exploration.

- Preplanning and front-loading the inquiry

Inquiry doesn’t mean “winging it.” In fact, good inquiry requires careful planning requires a lot of front-loading to anticipate the questions, resources, and learning experiences students will need. Admittedly teachers often spend time front-loading lessons, but it pays off exponentially when the routines flow seamlessly and students increase their independence over time through gradual release of responsibility. Teachers can front-load their planning by:

- Choosing rich sources or data sets students can analyze.

- Planning scaffolds such as graphic organizers, word banks, or guiding questions.

- Mapping out checkpoints (e.g., mini-lessons, small-group conferences) where skills can be taught “just in time.”

Because planning can feel intensive, many schools and teacher teams find success by collaborating. Sharing inquiry units, lesson plans, or source sets spreads out the workload and sparks fresh ideas.

Where are you on the inquiry continuum?

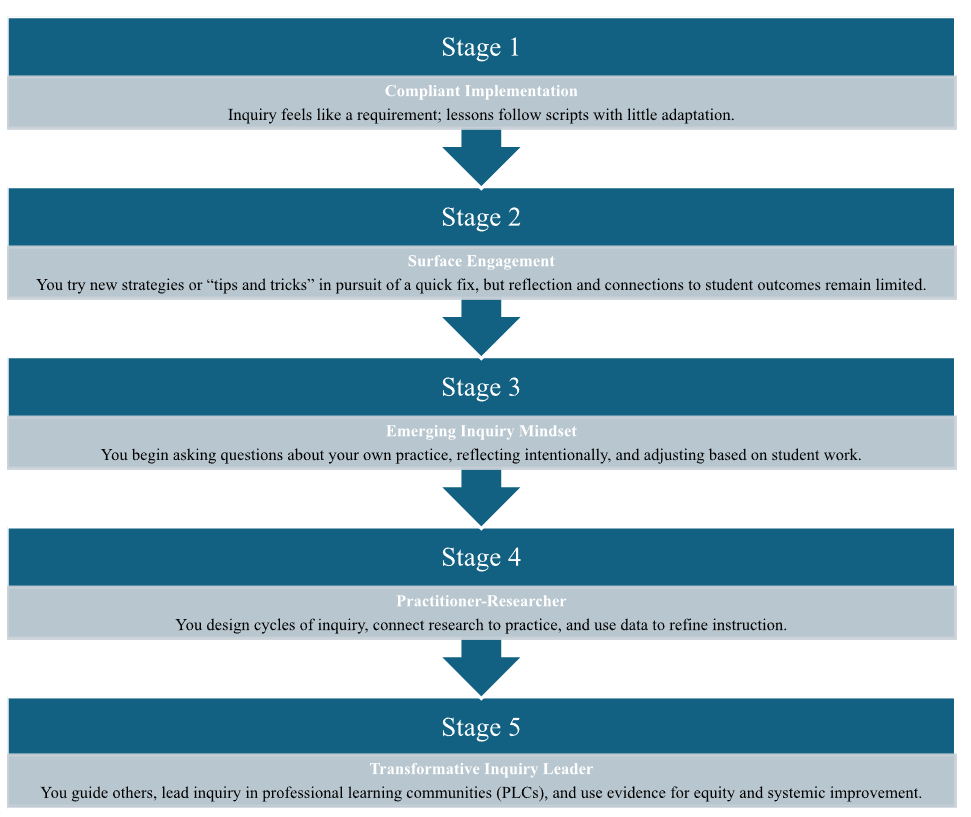

Every teacher approaches inquiry differently, and that’s okay. Think of inquiry not as a fixed method, but as a continuum of practice you can grow along. Use the Inquiry Continuum Self-Assessment we’ve developed to reflect on your current stage.

After completing the self-assessment,

- Which stage best describes where you are now?

- What small step would help you move toward the next stage?

- Who could you collaborate with to support that growth?

By identifying your place on this continuum, you can set realistic goals and celebrate progress; whether that’s trying a single inquiry strategy such as Question Formulation Technique (QFT), designing a unit-level inquiry cycle, or mentoring colleagues in inquiry design.

What Teachers Are Asking Now: Trends & Questions in Practice

Teachers aren’t just theorizing about inquiry; they’re actively asking practical questions and searching for resources. Google Trends shows some examples of current, real-life concerns:

- How do I choose a topic that will engage students?

Many teachers are experimenting with tools like Google Trends to find real-world hooks. For instance, a spike in interest for “educational inequalities” became the basis for inquiry questions such as “What are the consequences of inequality?” and “How can social inequalities be reduced?” - How do I balance inquiry with curriculum requirements and time constraints?

On forums like Reddit, teachers regularly voice concerns about fitting inquiry into rigid pacing guides and standards. Common questions include: How much of the lesson should be guided vs exploratory? and When should I step in with direct instruction vs letting students figure things out? - How do I scaffold inquiry for younger learners?

Research highlights a growing trend in inquiry-based learning at the elementary level, especially through STEM to foster critical thinking. Teachers are asking: What supports (routines, modeling, sentence starters) help younger students ask strong questions?

These questions show that inquiry isn’t just about “letting kids explore.” Teachers want practical ways to plan, balance, and scaffold inquiry so it fits their classrooms and students.

3 Ways to Use Inquiry-Based Teaching in Your Classroom

Now that we’ve defined what inquiry-based teaching is, highlighted its essential components, and looked at real-world teacher concerns, let’s explore three practical strategies you can use to bring it to life in your classroom.

- Start with better questions (and let students own them)

Try this: Launch a lesson with the Question Formulation Technique (QFT). Students rapidly produce questions from a shared prompt (photo, quote, graph), improve them, and prioritize a few to investigate. It’s a short, reliable protocol that builds curiosity and agency.

Post a focus (a stimulus to prompt students), set the four rules, run timed rounds, then sort open/closed questions and prioritize.

Why it works: Questioning is a gateway to inquiry; it develops metacognition and transfers across subjects. You can adapt QFT from kindergarten through AP.

- Investigate with primary sources (Observe/ Reflect/ Question)

Try this: Give students a compelling photo, map, or short text and use the Library of Congress Primary Source Analysis Tool. Have them Observe, Reflect, and Question, then list next investigation steps. It’s quick to set up and works in any subject.

Why it works: Students practice evidence-seeking and perspective-taking while building background knowledge. This routine is supported by Stripling’s “Wonder” and “Investigate” phases in the inquiry model.

- Run mini projects (1-2 weeks)

Try this: Design a short unit project around a real audience or local need. Example: “How might we welcome new families to our school?” Students research needs, prototype artifacts (infographics, videos, translated guides), and share publicly (family night, class website, or a partner classroom). This gives students an authentic learning experience and opportunity to collaborate and communicate with a real audience beyond the classroom.

Why it works: A public product such as a brochure, poster, or blog, raises relevance and accountability while giving students meaningful reasons to apply content knowledge and success skills (critical thinking, problem-solving, collaboration, communication, creativity).

In conclusion, centering inquiry is less about adding another teaching strategy and more about reshaping how students see themselves as learners. When evidence becomes the anchor and questions drive the work, students aren’t just meeting standards. They are practicing how to think, create, and collaborate in ways that extend beyond school walls. Inquiry invites them to step into roles as investigators, problem-solvers, and storytellers of their own learning, often demonstrating that they can exceed expectations. For teachers, it is a reminder that our most lasting impact comes not from the answers we provide, but from the questions we empower students to pursue.